American Foursquare

Address unverified

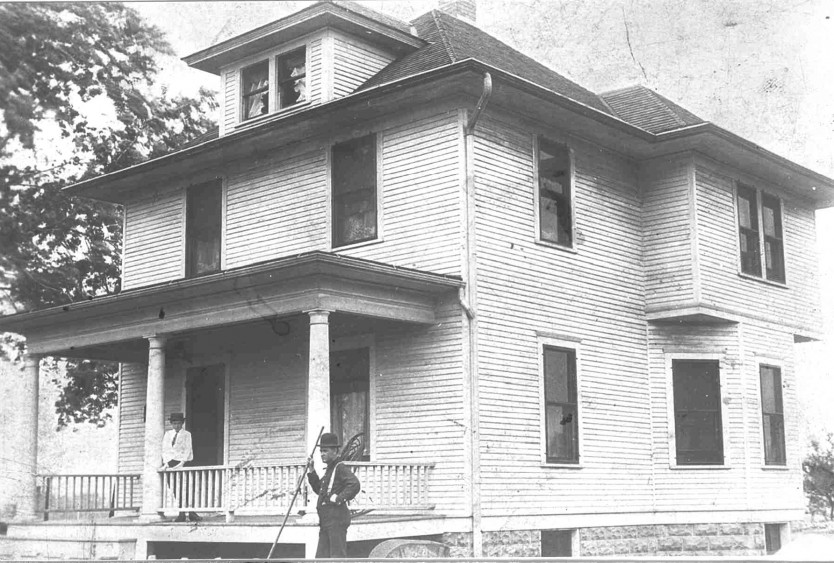

This Real Photo postcard is believed to show a Rock Island house, as it was included with many other Rock Island postcards that Robert Schroeder inherited from his grandmother, Emma Holtzer. Handwriting on the back identifies it as the “McKay House,” although City Directory research couldn’t find a Rock Island McKay family living in a home like this. Still this classic American Foursquare home just might be in Rock Island. Perhaps you can help find it.

American homes have been built in many architectural styles. Even while utilitarian log cabins or sod shanties were being built in the wilder regions, cities in the east and south had streets lined with elegant Georgian, Federal, and Greek Revival homes. Owners of small, modest homes, too, aspired to the high style decorations of their richer neighbors and added details such as columns, brackets, or a bay window to an otherwise plain house. Until about 1900, America’s residential architecture was influenced by European antecedents. The style names remind us of that — Second Empire, Queen Anne, Italianate. Even the “Federal” style had its roots in English styles popular during our country’s birthing years. We didn’t want King George any longer, but we still liked “Georgian” architecture.

And then came the American Foursquare, a house to fulfill the American Dream. Although that name wasn’t adopted until a couple of decades ago, this was a homegrown style that developed in the Midwest in the late 1800s and became one of the most popular and affordable styles nationwide. There are other names for the American Foursquare: The Box house, the Cube house, and, because of its popularity in the Midwestern states, the Prairie Box.

The essential form of the Foursquare is a cube covered by a moderately pitched hipped roof with wide eaves. The roof contains, at a minimum, a front dormer for the attic with the dormer roof a smaller version of the larger roof. There’s always a full width front porch, and, geography permitting, a basement. Exteriors were usually wood clapboard, but could be stucco, wood shakes, brick, or stone-textured concrete block. Sears Roebuck catalogues even sold special molds to cast stone-textured blocks. The stucco, brick, and concrete homes often used the siding material to cover porch supports.

Inside the Foursquare, there are four (could you guess?) more-or-less square rooms on each floor, each room with a corner exposure. The main floor has an entry hall with stairs, living room, dining room, and kitchen. Upstairs are three bedrooms and a bathroom. Woodwork and trim was typically relatively plain and, yes, square. Foursquares were economical to build – the most house under the least roof – and economical to heat and cool as well, thanks to the corner windows for ventilation and the minimal roof heat loss. Foursquares were a popular choice among those who bought “kit” homes from suppliers that included Sears Roebuck, Aladdin, Lewis, Harris Brothers, Sterling Homes, Bennett, and Davenport’s own Gordon Van-Tine.

The postcard house is a typical American Foursquare, showing all of the essentials of the style – cube shape; hipped roof with wide eaves; single dormer with roof matching the main one; wide porch with heavy columns and square balusters; double-hung windows; and concrete block basement. Its only enhancements are the flared roof edges, a shape called “bellcast,” and the two-story bay window, with a square bay atop an angled one.

The popularity of the basic Foursquare inevitably led to enhancements. A rear addition, often with a gable roof, enlarged the living area without significantly changing the Foursquare appearance from the street. More roof dormers sprouted. Although windows were usually double hung, bay windows, sometimes with a large fixed center pane, and stained or beveled glass. were a common addition. Foursquare homes incorporated elements of other styles, both old and new. Stucco or brick homes sometimes had “Tudor” half timbering, especially in gabled porch roofs. Brick Foursquares used trim at the second story sill level evocative of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie style. Palladian windows and classic columns created an instant “Colonial” Foursquare, while wood shakes and exposed rafters gave a “Craftsman” appearance.

Rock Island’s Foursquares can be found wherever areas were being developed in the early decades of the 20th Century. Many were built in groups by contractors who were careful to ensure that each home was slightly different from its neighbor. Often this meant varying porch columns — square, round, short or long, but always large rather than delicate “Victorian” types. Sometimes different dormer window patterns were used, or mullion patterns in the upper sashes changed from house to house.

A large concentration of Rock Island Foursquares is located on 14th Avenue just east of 44th Street. More Foursquares can be found just over the border in Moline. Although many of these houses have had their siding covered and their porches enclosed or even removed, the similarity of the basic form and the different enhancements can still be detected. Many other Foursquares are found in the Longview and Keystone neighborhoods. Perhaps one of our perceptive readers will find the McKay House among them.

This article by Diane Oestreich is slightly modified from the original, which appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on April 2, 2006.

March 2013

NOTE: After this article originally appeared, TWO houses were identified by readers. One reader identified it as here house at 503 21st Avenue. Her family had purchased it from the Buckles family, who had lived there for over 60 years, since a few years after it was built. Although it has been sided with newer wide siding, and the porch railings have been covered, the tall porch columns are the same as on the postcard and the form of the house is identical. Moreover, this house is located just up the street from Mrs. Holtzer’s home, so it is easy to think that she took the original photo on the postcard.

Another reader identified it as a house next door to him, at 2723 9th Avenue. It, too, has newer wide siding but the original porch is unchanged. It still has the tall round columns and square-spindled balustrade shown on the postcard. Like the first, the form of the house is identical to that on the postcard. The reader noted that a tree, which casts a shadow on the postcard picture, correlates with a large tree in his yard that has since been cut down. Moreover a small tree visible at the rear of the postcard house is in the same spot as a larger tree today. According to the year-end summary of new buildings in the Argus, the 9th Avenue home was constructed in 1911 for John and Mary Cunningham. It was described as “two-story frame, modern” and cost $3500. What “modern” means is undetermined; however not every house was described that way. Mr. Cunningham was a traveling salesman. For many years afterwards, it was the home of the Bregger family.

The original postcard had “McKay House” written on the reverse. As far as can be determined, neither of these homes has a connection with anyone named McKay. Perhaps a bit more detective work is needed to make that association.