Rock River Dam

Rock River Near 11th Street

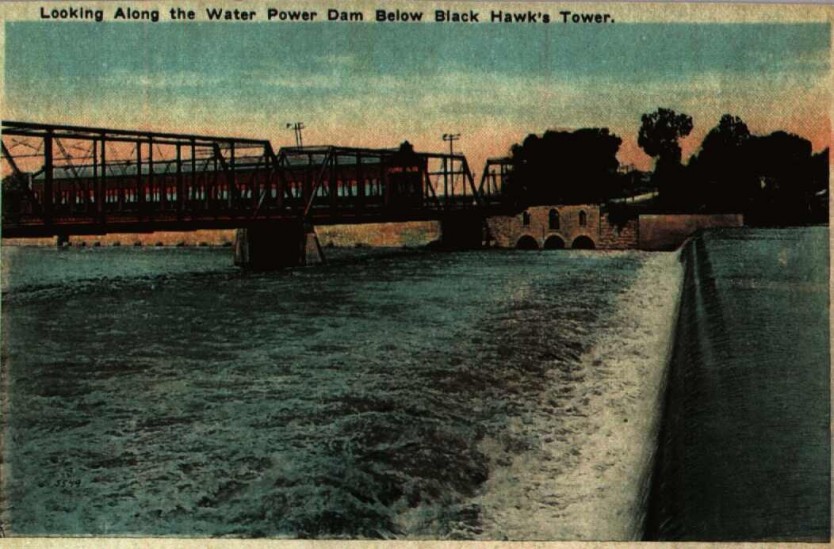

Although the postcard labels this the Water Power Dam, most of us call it the Sears Dam, sometimes the Sears Power Dam. It’s located in the Rock River just east of the Route 67 bridge from Rock Island to Milan and its name is a legacy of David B. Sears, dam builder and town builder extraordinaire. Mr. Sears was a visionary when it came to dams – he was determined that rivers should work, and he did his best to tap their massive power.

But Sears only saw the dammed river as direct mechanical power that would be used at its source. It took Samuel S. Davis and another 40 years to realize the full potential of a river, to convert the mechanical power of flowing water into electrical power that could be transmitted on thin copper wires throughout the community.

Thanks to Rock Islander Dick Iverson for sharing this postcard with us. Now, for the rest of the story.

David Benton Sears (1804-1884) came to Moline in 1836. Only a year later, with two partners, he began building a dam in the Mississippi river side channel known as Sylvan Slough, between the east end of the Rock Island (Arsenal Island) and the Moline shore. That dam, too, was known as the Sears Dam. Mr. Sears built a multipurpose mill on Illinois shore in 1838. It sawed wood, ground flour and carded wool.

Later, in 1843, he and his partners purchased more land and ultimately platted what became Moline. Before that, he had platted Rock Island Village on the eastern end of Arsenal Island. It had a steamboat landing, chair factory, warehouses, stable, and flour mill. Sears is credited for enticing John Deere and his partners to come here from Grand Detour by promising him free waterpower for his plow factory from the Sears dam. These accomplishments would have been enough for most men, but not for David B. Sears.

Once the U.S. government decided to build an arsenal and take over the entire island, Sears was forced to sell his land and dam. He was more fortunate than some other residents there who were only squatters, as he was well paid for his 35 acres. So now what should David B. Sears do? Well he’s a dam builder, remember, and there’s more than one river to dam.

Sears ended up on the Rock River, getting permission from the state to build four dams near its mouth. One of his dams was a few hundred feet upriver from the postcard dam, another was between the eastern end of Vandruff’s island and the Milan shore (now the Steel dam area), and the two others were small dams between the islands near Vandruff’s. The dams allowed Sears to direct the water where he could use it, into the canal (millrace) he had built next to the westernmost dam. As the newspaper put it, “(This) fine stream is prohibited from going to waste and is obligated to do its part toward advancing civilization.”

By 1868, Sears’ 12 foot high, $200,000 dam was finished and his five-story flour mill on the island just south of the millrace was nearly complete. The foundations of that mill, which burned around 1890 (reported dates vary), can be seen under the bridge in the postcard. In 1873, he opened a cotton factory on the north shore of the river that employed up to 100 workers, making everything from cloth to carpet warp. That building is still standing and was recently converted to senior housing.

Nearby and on Vandruff’s Island others planned and built papermills, sawmills, woolen mills, and more, and it was noted that 1 ½ miles of riverfront was suitable for mills. Each mill needed its own waterwheel. The power from the rotating shaft of the waterwheel could then be taken where needed in the mill using giant belts, pulleys, or gears. David B. Sears also platted the town of “Sears,” sometimes called “Searstown,” in 1869 next to his canal on the north bank of the river. Searstown was annexed to the City of Rock Island in 1915.

But now fast forward to October 29, 1907, when the Argus reported that grading and widening of the Sears Canal (the old millrace) had begun in preparation for a huge new electrical power plant under the auspices of Samuel S. Davis. Early in the 20th Century, S. S. Davis owned a great deal of land near Sears.

Rock Island natives S. S. Davis and his brother were visionaries. They saw the power of electricity and as a result brought many public utilities – electricity, gas, even water – to the various Quad Cities. They established a firm that has, through mergers and reorganizations, evolved into our MidAmerican Energy Company.

By this time, most of the old Sears mills had been abandoned. Floods and ice had damaged the old dams. And S. S. Davis, saw the Rock River wasn’t earning its way any longer. Moreover he knew he could use that wasted water flow to generate electricity that he could sell to his Tri-Cities Railway and Light Company. So he got an Act of Congress to permit his new company – the Rock River Navigation and Water Power Company – to build and rebuild dams and to improve the old canal, so he could build a power generating plant on Sears’ old mill island.

A new dam – the one on the postcard — was built closer to the bridges (the bridges in the picture are for autos and trolleys). The canal was deepened by 30 feet and widened by 51 feet. An overall water level drop of 14 feet was planned, although a later report indicates that a “head” or drop of 20 feet was achieved. It was also noted that the dam would be good “until the river runs dry.” The project entailed a great deal of work, money, and time. Finally, in 1912, the powerhouse was ready to produce electricity.

Although 13 or 14 power-generating turbines (basically an elaborate waterwheel, with specially shaped fins) were planned, an early Sanborn Fire Insurance Map notes that there are six generators. The map shows the powerhouse, and identifies it has having a concrete floor, exposed steel trusses, and a tile roof as well as a large “lightening arrestor” on the west side of the building. Greatly simplified, the powerhouse uses the rotating shaft of the turbines and magnets in a generator to create electrical current. The generator is a lot like an electric motor – except that instead of using electricity to create mechanical energy, it uses the mechanical energy of the turbine to create electricity.

In 1949, it was reported that the S. S. Davis Water Power Company was the third largest electric company on the Rock River, generating 2300 horsepower. There were a total of 63 waterpower dams in the 318 miles of the Rock River. The largest, in Dixon, generated 4000 horsepower while nearby Sterling generated 2800 horsepower.

At the end of 1958, heirs of S.S. and Apollonia (Weyerhaeuser) Davis donated the powerhouse to Augustana College. A few years earlier the family had donated the family home, now called the House on the Hill. Augustana operated the powerhouse until 1966, when it was closed because it because it cost more to generate electricity than the local power company would pay for it. The turbines were removed and Augustana donated the site to the state – and returned to its real task of creating power in the minds of young people.

In the late 1970s, it became economically feasible to consider reopening the powerhouse, thanks to President Jimmy Carter’s laws encouraging alternative energy sources to lessen our country’s dependence on imported oil. Now local power companies were required to purchase the output of small suppliers such as this at a fair price.

It still took a long time, but owners Mitch and Melba White were finally successful. After years of work – much of it done by themselves and family members, they installed new computer-operated turbine generators in 1986, and started producing power soon after. Although the windows are now covered, the powerhouse looks much the same as it did in our postcard. The bridges are different, and the old flour mill ruins are gone, lost when the new Route 67 bridge was built.

The dam? It’s pretty much the same, fortunately surviving a 1973 petition circulated by then County Board member John McChurch asking for the removal of both it and the Steel Dam in an effort to alleviate floods. And our beautiful Rock River is certainly earning its way. The Whites sold their facility to the City of Rock Island, which continues to generate electrical power there.

This article by Diane Oestreich is slightly modified from the original, which appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on December 2, 2001.

February 2013