Arsenal Power House & Dam

South Side of Arsenal Island

Some look at a flowing river and see beauty. Others see raw power ready to be captured. The waters of the Mississippi River have enormous power that is often untapped. The incessant current resulting from the drop in river altitude from north to south can be harnessed to produce energy.

Potential for water power depends on both the distance the water drops – called the “head” – as well as the volume of flow. Dams, which are built to create a larger head as well as ensure a reliable flow, mean that even small streams can generate power. Picturesque old grist mills with a vertical waterwheel still punctuate our rural landscape.

Power dams in larger streams use many rotating waterwheels or turbines. In the 19th Century, various mechanical means of transferring this rotation to useful energy were used. Today, water power is converted to electricity with generators that connect the shaft of the turbine to electrical wires which are then turned within a magnetic field to generate electricity. The opposite configuration, which uses electricity to rotate a shaft, is the common electric motor. Electricity is easy to transfer from one place to another.

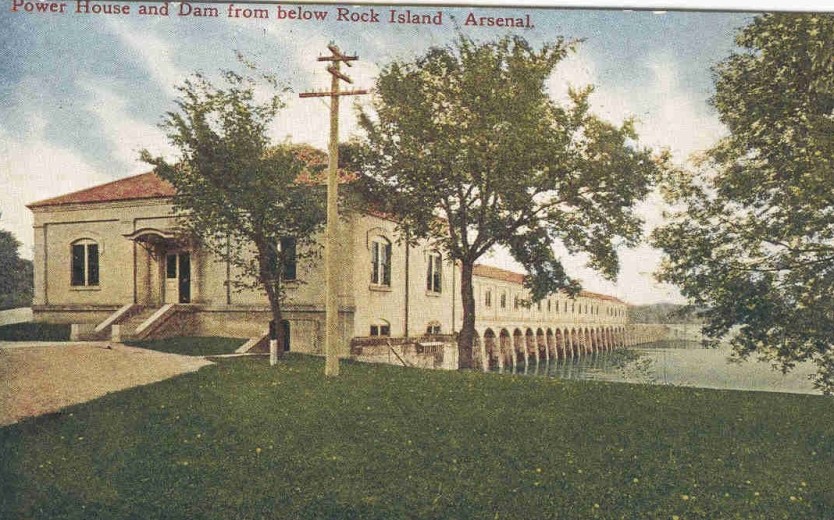

This colored postcard shows a water power plant that was built in the south branch of the Mississippi that we know as the Sylvan Slough. The site has been used for a power plant for 140 years. But even this spot was not the first use of Mississippi water power in the Quad City area.

David Sears, who would later found Searstown on the Rock River, began building a power dam in 1837 with two partners. The promise of power from that dam, which spanned Sylvan Slough between the east end of Arsenal Island and the Moline shore, is what lured John Deere and his plow factory to Moline. In the early days, the rotational motion of the waterwheels was transferred directly to giant rotating belts that were extended to factories. Because of the difficulty in transferring the power, factories were, of necessity, located very close to the power dam.

In the 1860s, plans were made to use water power from another dam between the tiny Benham’s Island and the northeastern shore of Arsenal Island. The intent was to use the water power to compress air which would then be used to power manufacturing. That idea was abandoned in favor of another dam, approved in 1872, to be built in close proximity to arsenal shops so the power could be more easily transferred. This dam was located in the same place as the postcard dam, between the northwest tip of what is now Sylvan Island and Arsenal Island.

Before the arsenal power plant went into use, the Moline Water Power Company had, with the cooperation and consent of the arsenal, built new facilities near David Sears’ old power works. Because the government required that the slough be left open for future arsenal power, it was necessary that a long lateral dam parallel to the shore be constructed. It was later found that the water behind the lateral dam became sluggish and stagnant. To increase the flow and remedy the situation, in 1872, the arsenal dug a new channel that cut off a portion of Moline below the dam and created Sylvan Island. Twenty years later, the Moline company removed the old dam structure and built a new power dam at the entrance to this channel.

Power was transmitted to the military shops from the arsenal dam using a “telodynamic” or cable system, which was installed in 1878. Rotation of the water-powered turbines was transferred to a 15-foot diameter drive wheel in the power house. Cables around that wheel were looped onto pulleys at the top of a wooden tower near the shops. From there, other cables looped to individual shops. Within each shop, a shaft near the ceiling rotated constantly, with individual machines engaged or disengaged from the shaft as needed.

The telodynamic system was cumbersome, inefficient, occasionally dangerous, and required much maintenance. In the 1890s, direct conversion of water power to electricity became an option. And when an 1899 fire destroyed the telodynamic system, it was an easy decision to switch to electrical power generation, which also coincided with the rebuilding of the power dam between Arsenal and Sylvan Islands.

This postcard, from the early 1900s, is a view of the downstream side of that dam as seen from Sylvan Island. The small power house is just a stone’s throw from the old arsenal shop buildings. A later addition on the Sylvan Island side was made about 1918.

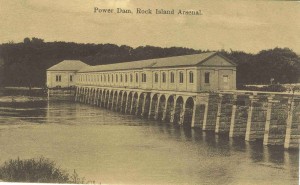

A second black and white postcard shows a view from the opposite side of Sylvan Slough. The 700-foot long utilitarian structure is surprisingly attractive, with graceful arches spanning the river. The best place to view this photogenic facility is from Rock Island’s newest park, the Sylvan Slough Natural Area. Dedicated last October, the park is located in a former industrial area south of the power plant where the man-made Sylvan canal enters the south branch of the river. In nice spring weather, it’s an easy walk or bicycle ride along the riverfront path from either Rock Island’s 24th Street or from Moline’s Sylvan Island entrance. The environmentally friendly park was created by a creative “deconstruction” of deteriorated industrial structures enhanced by plantings of native prairie grasses and flowers. Water runoff is managed by permeable paving and rain gardens. The park is well worth a visit on its own merits. Be sure to bring your camera.

This article, by Diane Oestreich, is slightly modified from the original, which appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on March 2, 2008.