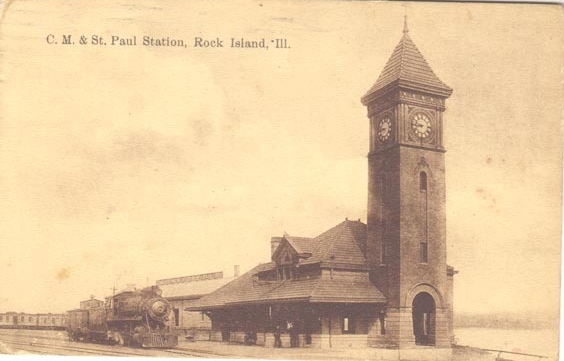

Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Depot

Foot of 17th Street

NOTE: The pictured postcard is not the one originally featured with this article.

From its earliest days, Rock Island was a city of railroads. With the railroads came their stations or depots, both for freight and passengers. The earliest stations were modest, utilitarian structures, but later ones were notable for their style and impact on the landscape. One of these former landmarks is the C M & St. P passenger station shown on this postcard from the collection of Dr. Mark Buckrop. It was prominently located on the riverbank at the foot of 17th Street, just east of what is now the Modern Woodman of America headquarters. The site of its freight house, visible on the postcard at the far left, is now covered by the MWA building.

The postcard abbreviation refers to the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad, although it was usually known as the Milwaukee station or, occasionally, the St. Paul station. When first built, it was called the D RI & NW (Davenport, Rock Island and North Western) station. The D RI & NW, usually called the DRI Line, was a local railroad company that was created in 1900, and jointly owned by the Burlington and the Milwaukee Railroads. It was responsible for building the Crescent Bridge and the remaining Moline Station, soon to be moved to a new site on the Western Illinois University campus on the Moline riverfront.

Winter of 1900-01 was busy for the railroad companies in Rock Island. In December it was announced that a large parcel of land on 5th Avenue had been purchased by the Rock Island Lines for its new depot, which would be completed a few months later. By mid-February, two new passenger stations had their grand openings. First open was the C B & Q station on 20th Street and the following day this postcard station held its celebration.

The largest, the C B & Q, was reported to have cost $150,000, while the mid-sized 5th Avenue station would have a price of $75,000. The D RI & NW (C M & St. P) had a final cost of $25,000, which included additional tracks and approaches. It was a stylish station, designed by local architect Olof Cervin. In September, 1900, prominent Rock Island contractor John Volk was awarded the $12,000 building contract, which did not include the cost of plumbing or electricity, and was allotted only 110 days for his work to be completed.

The Cervin-Volk team created a station of exceptional quality and durability, as would be vividly demonstrated half a century later. The Argus conservatively described it as, “Not large, but neat and handy, built of good material from bedrock on up.” Above a stone foundation, were walls of St. Louis pressed brick in a buff or tan color as shown on the postcard. According to Mike Jackson, architect with the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, such bricks were among the best quality ever made because of the pressure molds used to form the wet clay. Pressed bricks are distinctive because of their incredible smoothness and even color. The process is no longer used and is not likely to come back, because it was much more expensive than the modern extruded brick production methods.

A red tile roof covered the 96 x 40 foot one-story structure. A wide overhang extended over the railroad tracks on the south side and an even wider overhang extended toward the west. The main entrance at the east clock tower led through a tile-floored vestibule into the large waiting room, which held copper-roofed rounded bow windows on either side. One of these windows, which would have allowed panoramic views of the river or the tracks, is visible on the postcard.

A high oak railing surmounted by opaque glass enclosed the ticket office on the south east of the waiting room. Use of railings rather than partitions was said to make it look “more like a bank.” Farther west was a ladies waiting room on the north and a gents smoking room on the south. The baggage room, with a separate entry, was at the extreme west.

Quality abounded. Interior woodwork was of quarter sawn oak, while hard maple flooring provided durability underfoot. The colors were an artistic delight. Just picture the main waiting room: “Arched” ceilings were painted a sky blue above apple-green upper walls with olive green tiles on the lower walls. The ladies waiting room was similarly decorated except in shades of red rather than green.

The tower height was variously reported to be from 50 to 90 feet, but it was indisputably tall. It held a high quality four-sided Seth Thomas clock, warranted for five years to keep time within a minute a month without further adjustment. The 5 ½ foot dials were of translucent glass and were illuminated from within. The hands were driven by 300-pound weights, regulated by a 90-pound pendulum bob.

The clock did keep good time until a spring lightning bolt in 1945 stopped its hands forever marking 6:15. Time stood still until July and August of 1951 when it disappeared completely as the station was demolished. But Cervin and Volk’s tower proved the strength and durability of vintage construction, resisting destruction for hours.

After razing the depot, workers looped a steel cable around the tower and pulled it with a truck-powered winch, intending to topple it into the hole left by the depot. The tower held fast and simply pulled the truck wheels off the ground. So the truck was braced against a partially fallen wall of the old freight house and the task attempted again. Its engine overheated and only few chunks of brick were broken away.

It took eleven hours to fell this mighty tower, piece by piece. According to Marion Crist, owner of the demolition company, the two-foot thick walls were “glued” together with a specially treated lime mortar that welded the bricks into an almost solid mass. He estimated that there were 80 tons of brick and mortar in the tower.

John Ruskin, a 19th Century English writer and critic, wrote about building quality such as epitomized in this old railroad station: “When we build, let us think that we build forever……let it be such work as our descendants will thank us for.” Olof Cervin and John Volk followed that honorable philosophy.

This article by Diane Oestreich is slightly modified from the original, which appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on July 4, 2004.

March 2013