Clock Tower & Gatehouse – Arsenal Island

Rock Island – the real, the original, Rock Island – is the geographic and historical center of the Quad Cities. This is not some overgrown sandbar island-wannabee, subject to the whims of the Mississippi’s current. Rather, this sturdy thousand acre stone plateau that rises above the original shallow rapids forces the river to alter its path around it. Rock Island is the visible reminder of what created our community.

Aptly named for its solid rock underpinnings, Rock Island was revered by local Indian tribes. It held mysterious caves in its riverfront cliffs, with forests and rich soils above. It was home to the earliest European settlers, including Col. George Davenport. It anchored strategic Fort Armstrong, then on the western outskirts of the United States. It brought John Deere to Moline, with the promise of free power from its old dam. It provided the bedrock foundation for the first railroad bridge across the Mississippi. It served as one of the largest Civil War prison camps in the north. And, it has been a federal arsenal since the 1860s, with manufacturing capabilities exceeded by none, private or public.

Finally, it gave its name to our city and county and to other fledgling villages as well – Moline was originally called “Rock Island Mills” and both a “Rock Island City” and “Rock Island Village” existed briefly. Now, to avoid confusion with all the other Rock Islands, past and present, we usually refer to the original Rock Island as “Arsenal Island.”

In 1874, Mark Twain wrote about it: “The charming island…..three miles long, and half a mile wide, belongs to the United States, and the government has turned it into a wonderful park, enhancing its natural attractions by art and threading its fine forests with many miles of drives. Near the center of the island, one catches glimpses, through the trees, of the vast stone four-story buildings, each of which covers an acre of ground. ……..The Rock Island establishment is a national armory and arsenal.”

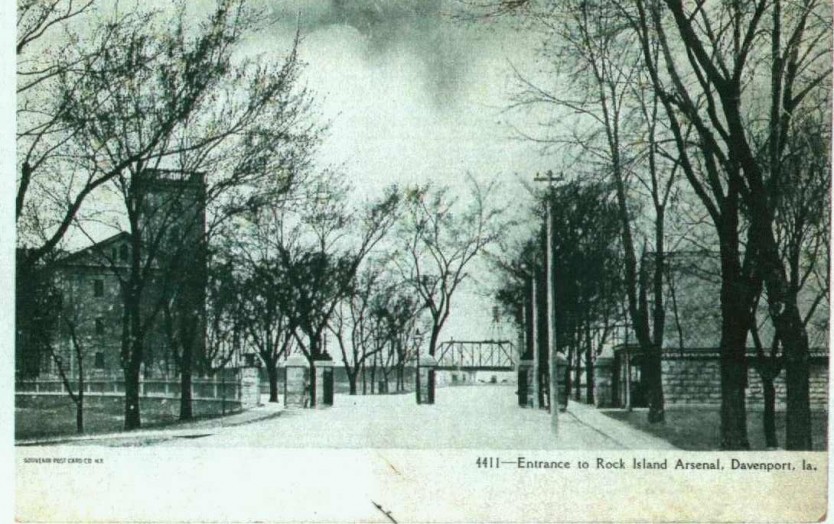

Since 1969, the entire island has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. An even rarer and more prestigious honor, its old limestone buildings are a National Historic Landmark. And one of these old stone buildings stands head and shoulders (well, at least a couple of stories) above the others. It’s the Clock Tower Building, located on the western end of Rock Island, which has kept vigil over the Island for 135 years, and is depicted on this postcard. Interestingly, although the postcard is captioned “Entrance to Rock Island Arsenal, Davenport, Ia.,” the Arsenal has always been considered to be in Rock Island and the picture, looking west on Rodman Avenue, is actually what one would see exiting the island.

Congressional legislation established an arsenal here in 1862 (an arsenal is a place for the manufacture or storage of arms and equipment). At that time, it was envisioned as a small facility for “deposit and repair” of ordnance (ordnance includes all sorts of military supplies, from weapons and ammunition, to vehicles and equipment). In 1863, Major C. P. Kingsbury, the first Commander of the Arsenal, arrived to construct the first permanent arsenal building, to be called Storehouse A. During that same period, the prison camp was being constructed on the western end of what is now the golf course. Much of the island was still occupied by private landowners as well as non-owning “squatters”.

An early drawing shows Storehouse A looking like much like the Clock Tower Building does today except for the roof, which had hipped rather than gabled ends. Construction of Storehouse A, which rests on the solid bedrock of Rock Island, began in September of 1863. It proceeded very slowly because, among other factors, construction materials were difficult to obtain and the prison camp construction and operation had a higher priority.

Maj. Kingsbury, who had who had been able to complete only the first floor, was reassigned in 1865. By then, the prison camp was closing. The second Arsenal Commander was Lt. Col. Thomas Rodman, sometimes called General Rodman, because of his honorary title of Brevet Brigadier General.

Col. Rodman, known as the Father of Rock Island Arsenal, resumed construction of Storehouse A. He requested a change to the previous army-approved design so he could add gables to each end of the roof. The gables increased the usability of the attic by providing ventilation and light. He also increased the height of the tower by 20 feet to accommodate the changed roofline and, in the bargain, make an even more imposing structure.

Although there are some references to stone being quarried on the island itself, the limestone for Storehouse A came from a quarry in LeClaire, Iowa. Stones were brought down the Mississippi to the west end of the Island. It’s also been claimed that wood salvaged over years from the original nearby Fort Armstrong (completed in 1817, abandoned in 1845, burned in 1855) as well as material from the Confederate prison camp went into the construction, mostly in basement window frames.

Storehouse A, now known as the Clock Tower Building, was finally completed in 1867. The recently restored clock that gives the building its name is original. It has four 12-foot diameter faces, hands of 5 and 6 feet, and a 3500-pound bell. The weights that drive the movement hang down three stories. The tower itself is 117 feet tall and twenty-five feet square. And it was designed for more than just holding the clock – it also supports a hoist to lift material to the main floors of the structure.

The other building, shown on the right in this postcard, is the gatehouse that was completed in 1875. Intended as the main west entrance to the island, it also could confine people who were charged with breaking arsenal rules. Originally it had a steeply pitched diamond-patterned roof, probably slate, with “gingerbread” under the eaves. A small front porch fronted the street, now called Rodman Avenue. Stone columns holding massive iron gates (folded back toward the viewer in the postcard) framed the street and sidewalks. Most of the stone columns and all of gates are gone, but the gatehouse remains, although without its porch and gingerbread and with a new roof.

The original plan called for other arsenal buildings to be at the west end of the island near the Clock Tower Building, but Col. Rodman believed the high land at the island’s center would be a better location. He went on to begin construction of the many stone manufacturing buildings and homes on the island. Limestone for these buildings came from many sources, including Joliet and Lemont in Illinois and Anamosa, Iowa. Unfortunately, Col. Rodman died in 1871 at only 56 years old, before all of his buildings were completed. He is buried at the eastern end of the island.

In its anniversary issue of November 27, 1912, the Argus carried a photo of the Clock Tower Building captioned, “Condemned Storehouse at West End of Island”. World War I may have provided a reprieve, as it continued in use until after the war, when the Army again proposed that it be razed. Objection from local residents, who recognized it as a major landmark, both from land and water, saved the building. It was finally vacated in 1930, but the Corps of Engineers moved into it in 1934, while the lock and dam was being constructed, and has remained there ever since.

Thanks to an Argus/Dispatch reader who submitted this postcard to us. Much of the information came from “An Illustrated History of the Rock Island Arsenal and Arsenal Island,” by Thomas Slattery, which was published in 1990 by the Arsenal’s Historical Office.

This article by Diane Oestreich is slightly modified from the original, which appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on November 25, 2001.

February 2013