House at 1103 2nd Avenue

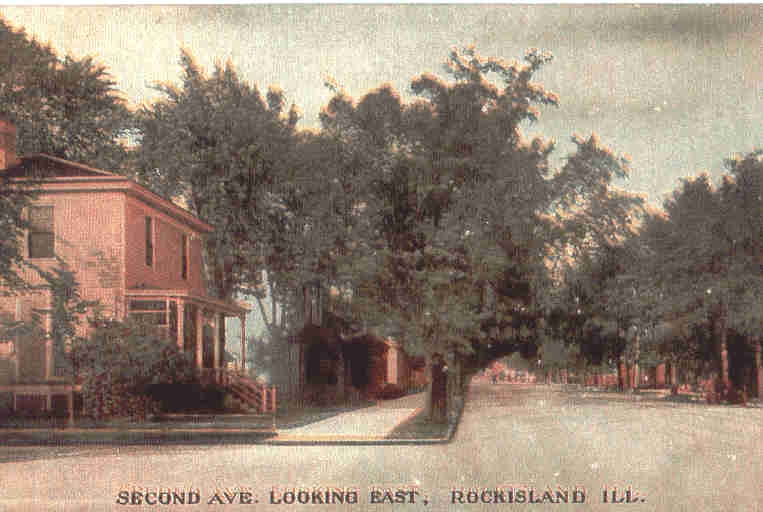

It’s a quiet street, a nice, tree-shaded street – and it could be anytown USA. But this postcard is a view of 2nd Avenue looking east from 11th Street as it appeared at the turn of the 19th Century. In some way, it’s a strange choice for a postcard –mostly trees and paving, it’s not particularly picturesque. Only one building is even recognizable, the corner house at 1103 2nd Avenue. It’s hard to imagine this postcard appealing to many people – except for the owner of 1103. But the postcard is interesting because it allows a story about the house and its inhabitants to be retold.

A hand drawn 1857 map shows a building on the northeast corner of what was then called Illinois and Swan Streets (The names weren’t changed to 2nd Avenue and 11th Street until 1876). It may represent this house as its Italianate architecture was the most popular style of the 1850s. The postcard shows a simple house, characterized by a low hipped roof. It appears to be frame, rather than the brick that was used so frequently in Rock Island for Italianate homes. Illinois Street was a premier location, and other homes in the area were generally much more ostentatious than this relatively modest dwelling.

The earliest owner who can be documented was Major General William Hoffman and his wife. Hoffman was a West Point graduate, a scion of a military family. His father, too, graduated from West Point. Maj.Gen. Hoffman had four brothers who were all army officers – and his sisters married army officers as well. According to Benton McAdams book, “Rebels at Rock Island,” Hoffman was appointed commissary general of prisoners in the Rock Island Civil War prison in 1861. It was said that he didn’t feed prisoners enough and even c Caused starvation. Althugh his reputation was of someone who intentionally denied care, McAdams researched indicated that he was not evil, but rather narrow, unimaginative, humorless, and wise in the ways of army politics. After the prison camp closed, Gen. Hoffman returned $1.85 million to the federal government.

In 1870 he retired from army and spent the remaining 12 years of his life here. He had been a widower but married a local woman who was a member of the prominent Buford family.

After he purchased the house at 1103, he began calling himself “Professor”. He was the principal (and perhaps the only) faculty member of an “Institute for Young Ladies,” about which nothing is known. Hoffman died in 1884 at the age of 76, but Mrs. Hoffman remained in the house for another few years.

The next owner of the home was L. E. West. West was an entrepreneur’s entrepreneur. Self styled as the “Hustler” he operated a factory at 1510-12 2nd Avenue (next door to the old post office) called the L. E. West Gum factory. An early street scene shows the factory building, covered with a huge painted sign saying “Chew Black Joe and White Sue Cream Gum”.

West’s advertisements in city directories didn’t mention chewing gum, but rather cigars, coffee, baking powder, and advertising items – an eclectic mix to say the least. When a fire destroyed the third floor of his factory in 1920, a stove spark was blamed for igniting the lacquer used to paint pencils. An Argus Town Crier article on Mar 24, 1943, featured a story on Mr. West who, at age 89, still hadn’t retired. It told how he got started in business – by writing and publishing sheet music in the 1890s. A real hustler and opportunist was L.E. West.

Mr. West had a daughter named Ruth. Ruth mailed this postcard to one of her school chums in 1907, inviting her to a Literary Society meeting with an informal reception for the high school teachers, to be held at 1103 2nd Avenue. Ruth was probably about 16 at the time. Ruth appears again, in another Town Crier of July 19, 1951. Now Mrs. C. M. Rogers of Chicago, she has two letters signed by President Abraham Lincoln. One letter discusses the possibility of a military promotion, the second says only “Let Mr. King bring the papers of Lewis B. Dougherty.”

And how did Mrs. Rogers acquire those papers? She had found them years ago, hidden in a metal box that was concealed behind a removable stone in the basement of 1103. The speculation is that they were hidden there by Maj. Gen. Hoffman, since the details of the promotion letter are compatible with Hoffman’s 1865 promotion. But who is Lewis B. Dougherty? What has happened to those letters since 1951? And could there by more letters secreted in hidden cubbies in the basement of 1103. We will never know the answers to the last question. Major General Hoffman’s house is gone, its site now part of the embankment of the Centennial Expressway.

This article by Diane Oestreich is slightly modified from the original, which appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on October 21, 2001.

February 2013

POSTSCRIPT: After this article appeared in the Argus/Dispatch, the following was received from Michael Kobbe:

I read with interest your article about the house at 1103 Second Avenue, Rock Island as its first owner, MG William Hoffman is my great grandfather. His daughter, Isabella, married MG William Kobbe from whom

I descend. Your article asks who is Lewis B Dougherty and is silent on the content of one of his letters.

An answer might be, since the article implies that two letters were related to Hoffman, is that he was the sutler at Fort Laramie, the letter was to his father, a major in the Army, and commented on the “Grattan Massacre” by the Sioux in 1854. Grattan was a lieutenant assigned to the Sixth Infantry stationed at Fort Laramie and my great grandfather William Hoffman commanded the Sixth Infantry at the time of the massacre and he was required to conduct an investigation.

A copy of the letter was published in the 6 October 1854 Liberty, Missouri Weekly Tribune and can be viewed at: http://cdm.sos.mo.gov/cgi-bin/showfile.exe?CISOROOT=/libertytrib&CISOPTR=117709#search=%22dougherty%22