Old Cable Mansion

…………………2915 Fifth Avenue………………..

Philander Lathrop Cable died on May 21, 1886, less than a week after John Deere was laid to rest. The Argus stated that, “What Mr. Deere was to Moline, Mr. Cable was to Rock Island.” Both men were born elsewhere, but reached their business, financial, and personal heights in their adopted cities. Each was an indisputable genius and civic benefactor.

P.L. Cable arrived in Rock Island in 1856, with his friend Philemon Mitchell, carrying cash with which to buy a bank. They bought the bank, but Cable soon decided opportunity lay elsewhere. He sold his bank stock to Cornelius Lynde in 1860 and invested the proceeds in the local coal mining industry. But coal is worthless until it is reaches someone who needs it. Railroads, which had already reached Rock Island and crossed the Mississippi, were the perfect way to transport this heavy black gold — and other commodities as well. Cable saw the potential. He began buying railroad stock, starting with the small Rock Island and Peoria line. Eventually he and his nephew, Ransom, were major owners of railroads throughout the country, including the famed Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad, commonly known as the Rock Island Line.

Around the time he sold his bank interest, Mr. Cable purchased a brick house that had been built by Lemuel Andrews in the mid-1850s on the north side of Moline Avenue, at an address that would later be known as 2915 Fifth Avenue in the Greenbush part of Rock Island. The Andrews home was built near the site of the Barrel House, one of the earliest buildings in what would become Rock Island. Reportedly the large lot was enhanced with a natural spring and a small creek. The house was set far back from Fifth Avenue on the north side, with the main façade shown on the postcard facing west. (The area is just west of Abbey Station, and is occupied by the former bus barn building as well as some railroad sidings).

According to Pamela Langston, writing in the local history book, “Joined by a River,” the Andrews house was completely renovated and redecorated for the Cable family, which included wife, Mary; son, Ben T.; and daughter, Lucie. A new gabled roof and a portico or porch with marble steps was added to the exterior. The interior was gussied-up with marble mantles and elegant cornices. Bathrooms were added as well, including perhaps the first built-in bathtub in Rock Island.

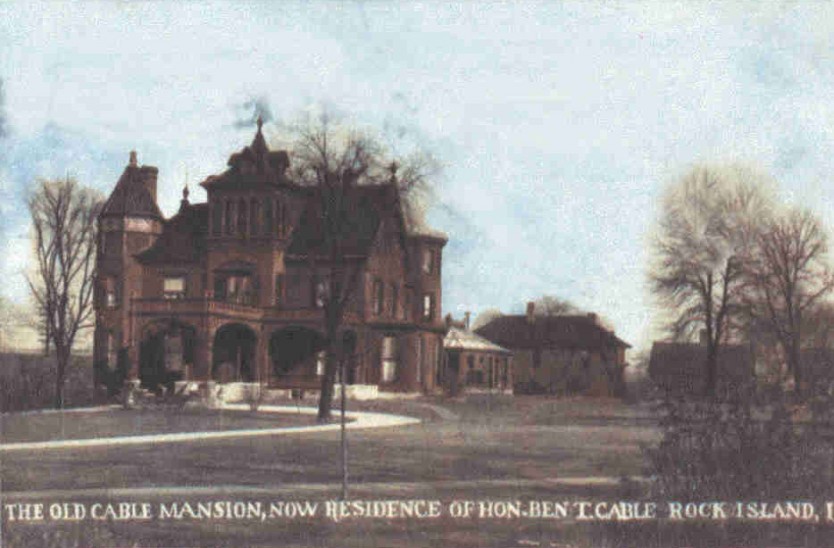

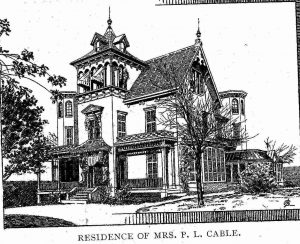

Our early 1900s postcard from the collection of Shannon Hall shows the front of the house as viewed from the southwest. The center tower that faced 29th Street was likely original, but the gabled roof and the porte-cochere at the front were added by the Cables. We can see two other towers, and, according to Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, there was yet another tower at the far rear. A large glass conservatory is visible at the right rear of the house. A drawing that appears in the 1888 book “Illustrated Rock Island” identifies the house as belong to Mrs. P. L. Cable. It does not yet have the porte-cochere or the pyramidal top on the left tower, which looks like the one at the rear. The solarium is there, but may have a slightly different roof.

Two buildings, both residences, are in the right background. The closer one was a large home that Mr. Cable reportedly had built for “Aunt Rachel” a former slave whose freedom he had purchased. After her death, the building was converted to private billiard rooms. The farther building was the gardener’s house. The Cable property also had an icehouse as well as a large carriage house. A siding from the several rows of railroad tracks at the rear of the property extended right into the carriage house so the Cables’ personal railroad coach could glide inside.

In his later years, P.L. Cable was afflicted by disabilities resulting from a fall. He set out for Monterrey, Mexico (in his private railroad coach, of course) where he hoped to find a more healthful climate. En route, he stopped in San Antonio, Texas. The San Antonio climate proved healthful, indeed so comfortable that he bought a thousand-acre ranch and, in 1883, built an 18-room home where the family wintered for the next 35 years.

After Mr. Cable’s death in 1886, his wife Mary remained in their Rock Island house until she died in 1895. The house was then known as it is captioned on our postcard — the residence of Hon. Ben T. Cable. The title came from his 1890 election to the House of Representatives where he served one term. When Ben became an invalid around 1920, he added a three-story elevator at the northwest corner, but only used it for three months before he died in 1923. His funeral was held in the home, by then known as 2903 5th Avenue.

Ben’s wife remained at the home until her death in 1934. Their son Philander, who had been born in France, had already left the Rock Island area. He graduated from Harvard and joined the State Department in the Foreign Service. He was only 49 when he died in 1940.

After Mrs. Cable’s death, the house was vacant for seven years. Then, on June 7, 1941, Argus columnist George Wickstrom wrote an “obituary for Rock Island’s most famous house.” The Cable house was going to be demolished and the land used for industry. The profusely illustrated article is worth reading in its entirety. Although the home had been vandalized during its vacant years, many of its fine details, from the mahogany paneled original bathtub to the rare, perfectly circular, three-story staircase, were intact. Family furnishings that had been left in the house were unaccounted for, although vintage carriages, many from France, were still in the carriage house.

Mr. Wickstrom also noted that the large San Antonio house had not been used by Cables since 1918. Much of the ranch land had been sold, and the house was rented for only $10 a month. Weeds grew in outbuildings.

A few days later, Mr. Wickstrom wrote another story, reporting that the vandalism was now complete – not by the paid housewreckers but rather by the community. After his first story, an estimated 4000 citizens had descended upon the house like locusts, ripping out or destroying everything of value that remained. The staircase was carried off in pieces, grabbed up randomly by souvenir seekers. Outside, railings from the first to the third stories were stolen. Shards of glass hung from the steel framework of the conservatory roof.

The wrecking ball was an anticlimax. The site of P.L. Cable’s mansion is now occupied by a Mid-American Energy building and the surroundings are industrial. The railroad tracks at the rear, although fewer in number, are still in the same place, but the private Cable siding is long gone.

In closing, we note another commonality between P.L. Cable and John Deere. Both purchased homes that had been built by others and both extensively remodeled and expanded their homes. But there’s one big difference. Mr. Cable’s house is only a postcard memory. Mr. Deere’s Moline house still stands, at 1217 11th Avenue, well on its way to full restoration. For that, we thank the many Moline preservation activists who have supported this restoration.

This article by Diane Oestreich, slightly modified, originally appeared in the Moline Dispatch and Rock Island Argus on September 21, 2003.

————————————————————————————————————————————–

ADDENDUM August 2017

We have learned more about “Aunt Rachel” as well as Mary Cable’s family, thanks to information provided by Blake Wintory, of Lakeland Plantation, an Arkansas State University Heritage Site http://lakeport.astate.edu/ . Following are some excerpts from his emails.

“I saw your 2003 article about the Cable House online and thought I’d reach out. You mention P. L. Cable built a house for Rachel a former slave and I see her and her husband and a black cook named Harriet in the 1860 census. But what sparked me to write just now is a memoir by Mary Cable’s niece, Emma Peak. Peak writes about a cook named Jinny on their plantation at Leota, MS on Mississippi River who visited “Aunti Mary” when she “went to live at Rock Island…[and] went to see her and then refused to leave her and stayed with Aunt Mary until she died of old age. I’m not sure when Jinny would have arrived at Rock Island, perhaps it was between censuses and she wasn’t recorded.”

“My interest is Mary Taylor Cable and Lydia Taylor Johnson were sisters (Emma Peak was their niece? thru a third sister Anne Taylor Worthington). Lydia’s husband, Lycurgus Johnson, corresponded often with P. L. Cable. We have four letters written by Cable to Lycurgus from 1858-1868.

“In the 1860 Census, Rachel is Rachel Dickinson, 64, “wife of old Black Servant” [James Dickinson] born in KY. Harriet Keene, the cook, is 44; also born in KY.

The 1850 Census for Mary & P.L. in KY doesn’t list any African Americans (slaves). The time frame is not clear from the memoir. Emma writes like she remembers slavery, but she wasn’t born until 1861. So she must be recounting family stories. Mary and P. L. moved to Rock Island in the 1850s, so I’d suspect the event is during that decade. Later, Emma and her husband lived at Wilton Junction, IA near Rock Island and might have seen Jinny during visits to her aunt. There might be more about Jinny in the memoir.” (Maybe it is later….Emma married in 1886 at the Peakland Plantation in Chicot County, AR and in describing her wedding, she says “A young girl had followed Aun’ Jinny the cook… )”

“Here are transcriptions of the letters Cable wrote to Lycurgus (his brother-in-law): https://docs.google.com/document/d/1kXJAS5yded0GUQuBLKUflPpxqB_m6vjHJDnVfrZf450/edit?usp=sharing Lots of financial talk, but the “best” line is from 1868 is ‘I thought that you were all fooling away your time in trying to make a living by settling with free negroes.’”