Roller Dam & Locks

Mississippi River

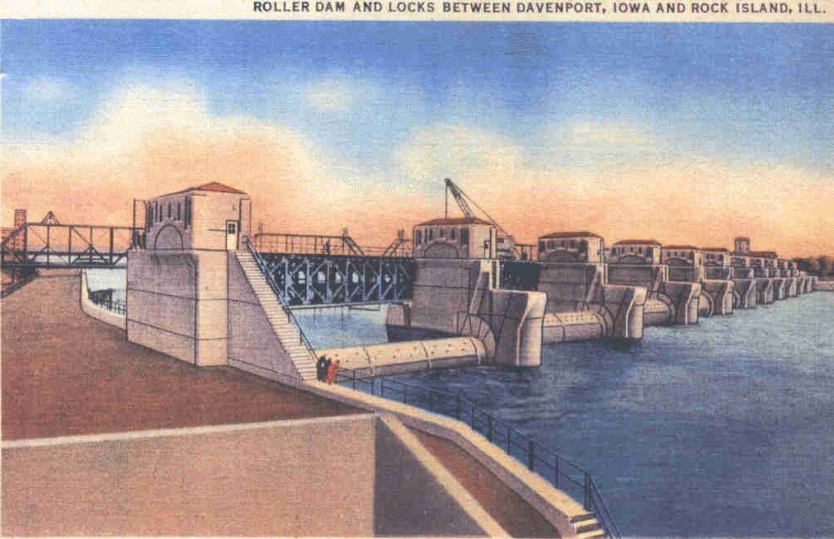

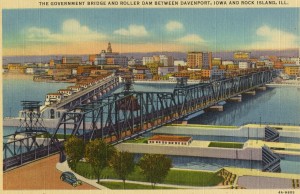

The featured postcard, and the one below showing a different view, represents the culmination of a century of navigational improvements on the Mississippi River. It was published in 1934 when the new Lock and Dam No. 15 opened at the western end of Arsenal Island and shows the downstream side of the roller dam, looking southeast from the Davenport side of the river. The old double-decker auto and railroad bridge is visible in the background. Most of the information for today’s column comes from Dr. Roald Tweet’s 1975 book, “History of the Rock Island Corps of Engineers.”

The Mississippi River has been used as a moving highway since the earliest days. The first simple rafts and canoes could operate when the water was only a few inches deep. Later vessels, including the picturesque steamboats that have become an icon of the river, were designed to operate in depths of only a few feet.

But as industry and agriculture along the river increased, so did demands for deeper and wider boats and thus deeper and wider navigational channels. Wing dams that extended part way into the river from its banks and forced the rapidly flowing water to scour the channel clean helped. But wing dams didn’t solve the problems of rapids, where rocky shoals near the surface covered by fast moving water could dash a boat to pieces. Rapids were improved in two ways – by breaking and removing rocks to make the bottom deeper or by building locks and dams to make the river level higher.

In the previous fifty years, several locks and dams had been built elsewhere, including Le Claire, Iowa. But the 9-foot channel authorized and funded by Congress in 1930 meant something had to be done about the Rock Island Rapids. The solution? A new lock and dam right here, the one on this postcard. The two locks were built shortly before the dam, so river traffic would not be interrupted. Both locks were 110 feet wide, with one 600 feet long and the second only 370 feet long.

Construction on the dam began in 1932. Earlier Mississippi dams had used a combination of gate designs but this was found to create problems, so the Rock Island dam used only roller gates. Additionally, roller gates were considered structurally sounder than other movable types. Strength was especially important at this part of the river where the narrow channel was subject to ice jams.

Basically the roller gates are long cylinders with steel teeth on each end that rotate into racks set into the side of the intermediate piers. To control the flow of water beneath the rollers, they are raised and lowered by chains at the ends powered by electric motors in the piers. Beneath the rollers are long steel plates, 13 feet wide on the upstream side, with a threshold or sill that the rollers rest against when the roller is fully closed.

There are eleven rollers, each nearly 100 feet long. The rollers on either end are only 16 feet in diameter, while the others are about 19 feet. The larger rollers never overflow, but the end ones, called “skimmer gates,” are designed so that continuously overflowing water will keep the surface of the upper pool clean. These two end gates are always kept slightly raised as well, so that some water flows under them. This is necessary to ensure good water motion past the supply intake in Illinois and the sewer outlet in Iowa.

Water never flows over the central rollers, which are adjusted to maintain a minimum channel depth of 9 feet in the upper pool. As the flow of water from upstream increases, these roller gates are raised gradually, beginning with the center one and moving outwards to allow excess water to escape underneath.

The continuous steel “bridge” along the upstream side supports a large electric crane used to service the machinery as well as to remove any large debris that accumulates. A smaller crane along the lower part of the service bridge is used to place emergency bulkheads in slots built into the upriver side of the piers. These bulkheads hold back water when a roller must be removed for repair.

The larger structure at the south end of the dam is the control house. It contains a small water power turbine that generates electricity for lock operation, as well as backup power systems. The total cost of Lock and Dam 15, which opened in spring of 1934, was nearly $7.5 million. Compare this postcard with the dam today. It looks the same.

This article, by Diane Oestreich, is slightly modified from the original that appeared in the Rock Island Argus and Moline Dispatch on March 2, 2003.

February 2013